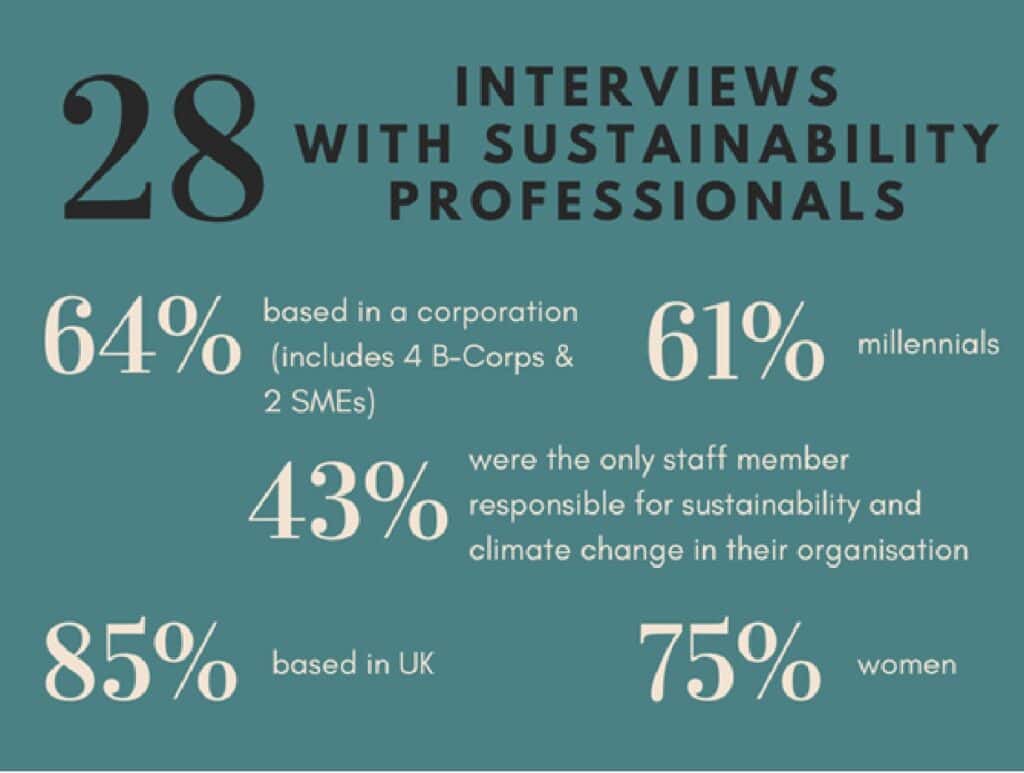

In early 2024, we asked 28 in-house sustainability professionals about their work. They outlined five common challenges.

A recent research project explored the personal experience of sustainability professionals, to better understand their challenges and state of wellbeing at work.

Our participants had experience in various types of organisation – large government departments, corporates and B Corps. They were also at different career stages: 12 had worked in the environmental sector for under four years; 11 for four to ten years; and five for over ten years. While our sustainability professionals differed in age, gender, race, and employer, we identified five key challenges they all faced.

1. Eco-anxiety – feelings of sadness, worry, guilt, disgust, and anger in response to environmental and social breakdown were common.

Participants frequently reflected on how working on climate change created “stress that is above and beyond the normal stress of work.” One Chief Sustainability Officer said: “uniquely in this job, compared to another job where there’s a lot of emotional responsibility, for example being a doctor, is that this is all-encompassing – it doesn’t end with one patient, it’s everything. And then that is coupled with a general lack of awareness in lots of people.”

Some struggled with existential concerns and depressive feelings, and felt heavily burdened by climate action in their work and life.

While not everyone identified with the term eco-anxiety, many participants commented on how they felt they had to ‘mask’ their feelings about the climate crisis at work to avoid burdening or upsetting colleagues and collaborators.

2. Internal greenwashing – communication that misleads people regarding environmental performance or benefits of an organisation.

Participants most often experienced greenwashing within organisations, rather than in the marketing of sustainability credentials.

One way in which internal greenwashing was experienced was the receiving of verbal support or commitment to ambitious targets from leadership, but then subsequently receiving insufficient staff allocation, official key performance indicators (KPIs), or financial resources to fulfil commitments.

Interviewees commented that organisations were more focused on sustainability initiatives for marketing, or box-ticking for regulation or investor requirements, than in making meaningful change.

This led to participants asking themselves what is ‘enough’ for sustainability, and whether they themselves were contributing to greenwashing.

Without direct line management responsibilities or solid KPIs to hold the wider team accountable, they needed to spend a lot of their time influencing or persuading others on sustainability issues.

3. Loneliness – most participants shared a sense of loneliness and of feeling like an outsider at work.

For some, a lack of leadership on sustainability within their organisation meant they felt alone in their efforts, particularly when leadership deprioritised or cut sustainability team budgets. In some cases, participants felt their enthusiasm to drive change was held against them.

Where managers were more supportive of sustainability professionals driving several initiatives, the participants’ enthusiasm, combined with too much autonomy, led to overwork and burnout.

While participants found connection in other networks, being solely responsible for sustainability in their organisation was exhausting. There was a sense that the scale of work involved to implement sustainability required a team, but 43% of participants held the only explicit ‘sustainability’ role in their organisation.

Many participants said it felt like extra work to be responsible for explaining different sustainability topics to co-workers. Having just one other staff member responsible for sustainability in an organisation made a huge difference to improving motivation. These experiences of loneliness were mentioned by people at all career stages, and even by those who worked in a sustainability team with more than one person.

4. Imposter syndrome – the feeling that participants didn’t know ‘enough’ about sustainability.

Imposter syndrome could arise early in participants’ careers, due to the volume of information and training (or lack of training). Or, as their awareness of sustainability’s complexity grew, or the breadth of their role expanded, confidence would decrease.

One interviewee exclaimed: “You want to call me a sustainability expert? This is a huge topic. There’s almost nobody in the world that is a sustainability expert.” Some participants acknowledged how new an industry sustainability was, and how rapidly changing requirements made it ‘impossible’ to be an expert.

5. Career progression and expertise being appropriately compensated was another major challenge.

Job stability and pay were issues for those working in the third sector, non-profits, or local government, yet a lack of clear promotion pathways and funding were also mentioned in corporate settings. Job insecurity and low pay were emphasised in other ways. For example, several participants acknowledged they worked in this sector thanks to personal circumstances such as having a spouse with secure employment, financial support from parents for housing, or having few caring responsibilities.

Together, these challenges shine light on the experiences of sustainability professionals. While educational institutions and professional associations provide ample guidance on technical skills for creating sustainable organisations, the five challenges we observed highlight that more support is needed around soft skills related to personal resilience, motivation, and persuading others to take action.

This is a guest article by Katherine Ellsworth-Krebs (Coach for Sustainability Professionals and Chancellor’s Fellow in Sustainable Design at the University of Strathclyde), Heather Lynch (Coach and Facilitator for Sustainability Professionals), and Shona Russell (Senior Lecturer in the School of Management at the University of St. Andrews and Co-Director of the Centre for the Social and Environmental Accounting Research).

Want more ideas about how to support sustainability professionals? Read more about our research; subscribe to our newsletter; or follow us on LinkedIn! Katherine Ellsworth Krebs; Heather Lynch, and Shona Russell.

Image credits: Image 1 = Shutterstock, Image 2 (statistics) provided by authors

Related articles

How to build a sustainability team that delivers

Transferable skills: essential sustainability competencies to master